After years working, filming and living on the African continent, I returned to North America in 2012. Having followed Obama’s election in 2008 from afar, I was fascinated by the impact it had seemed to have across the world. I decided to spend time canvassing for the presidential campaign in low-income neighborhoods of Ohio and Pennsylvania so that I could see the effervescence up close for myself.

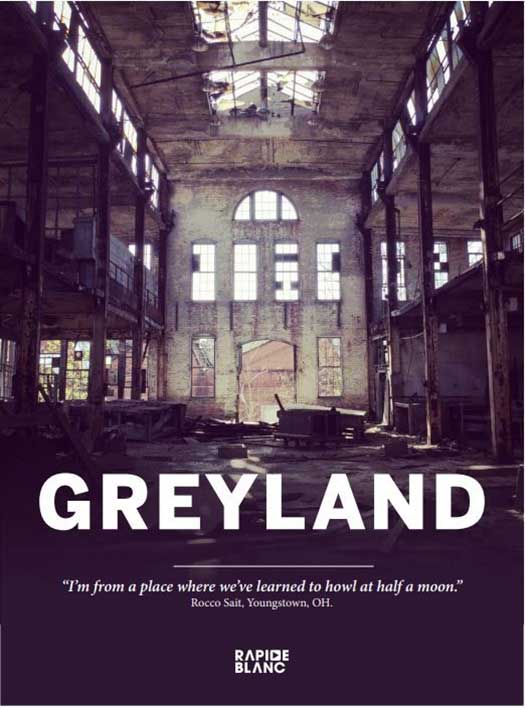

But instead, I was shocked by the social injustices and societal breakdown I witnessed. Like most, I knew of the devastation of the economic crisis affecting the US, but I wasn’t prepared for what I heard and saw: a destroyed social fabric and loss of pride. What I was witnessed, was the breakdown of the modern world’s social contract, following the rise and fall of industrial power. There is no doubt that the United States provides many powerful and overbearing symbolisms around the world—yet, it seemed we never fully delve into the other side of the coin. As an outsider, and especially as a Quebec native who lives just on the other side of the border, I felt I could offer an external perspective that resonates with the future the world is confronting, beyond America’s borders. I felt it was time to take a symbol as strong as the one offered by the United States and look at it through a magnifying glass in order to tell a much larger story facing humankind.

For this reason, Youngstown was the perfect laboratory for such an observation. Small enough so that all the social and political issues present elsewhere would be concentrated at a level not found in bigger cities. I approached a colleague, Professor Justin Gest, who had spent several months in Youngstown, interviewing residents for his book “The New Minority.”

With the social breakdown that has affected the city, Youngstowners are wary and suspicious of outsiders and locals alike. The initial research for the film benefited from a relationship Professor Gest built with people in Youngstown’s government and civic organizations, as well as his acquaintance with the city’s history, politics and economic trends. Thanks to the respect that Prof Gest research had gained, we immediately had access to several people in Youngstown, such as Rocco and Amber.

Over the course of nearly six years, the film’s characters have perceived our camera as a confessional. During shoots, only Katerine Giguere (Director of Photography), and I are present, creating a safe and intimate space with our characters. We are nearly the same age as Rocco and Amber and our ideas on filmmaking closely align with many of their own aspirations to create change. As we have returned to Youngstown several times over the years, they have become to trust our vision for the film. I regularly keep in touch with Rocco and Amber via text messages and occasional phone calls. As many anthropologists or ethnographers do, I’ve allowed Youngstown to inhabit me over the years. The complex relationships and thoughtful intimacy that one can create with people one may not initially have much in common with is what compels me to make documentaries. Openness and trust built over time is what has allowed me to provide a profoundly human, truthful and intimate perspective on an important story of our times.

Alexandra Sicotte-Lévesque

Alexandra Sicotte-Lévesque